The industrial techno revolution

Karenn, Surgeon, Truss and Perc discuss the recent return of the diesel-powered sound.

There’s something in the air in the UK, and it doesn’t smell very pleasant. Is it the hot odour of amps overheating, speaker cones crumbling under sustained abuse? Or the smell of sweat and stale cigarette smoke clinging to stained carpets, the musk of fight-or-flight responses in cramped basements and dilapidated warehouses?

Whatever it is, no amount of Febreze is going to shift it. 2012 was the year that AnD and MPIA3 threw caution to the wind and plunged headfirst into churning primitivist rave-techno. It was the year that Perc Trax cemented their stern aesthetic with releases from Forward Strategy Group, Dead Sound & Videohead and others, and Perc himself released a raging acid-techno track titled “Pure & Simple.” It was the year that Surgeon and Regis’ British Murder Boys project made a triumphant return, Shifted and Ventress’ Avian imprint reached new heights of aggression, and Blawan inspired a legion of youngsters to toughen up their kick drums. British industrial techno had been born again, and 2013 may be the year it takes over.

Perhaps the most visible proponents of this re-emergent sound are the duo of Jamie Roberts and Arthur Cayzer, AKA Karenn. Both came up as solo entities in the wake of dubstep—Roberts as Blawan, Cayzer as Pariah—and were initially known for garage- and house-inflected hybrids for labels like Hessle Audio and R&S. Blawan has since followed his muse into far darker climes, refining the aggy inclinations of his earlier work (see 2011’s “Bohla”) into a unique and hugely popular take on warehouse techno. The Karenn project pushes things even further. The project’s second EP, Sheworks 004, released late last year on the pair’s own imprint, features six alien-sounding analogue techno cuts that both echo and radically overhaul the soot-blackened sound of the mid-’90s. What’s most striking is the audience for this music: often young émigrés from the post-dubstep dispersal, for whom techno of any form—let alone of such an uncompromising kind—is an entirely new experience.

So were industrial flavours always part of Cayzer and Roberts’ tastes, or a recent discovery? “I think both of us come from a background that relates to industrial music, more so, you could say, than our dubsteppy and garage tracks,” Roberts says. “Cabaret Voltaire were a pivotal moment for me. From there I found Throbbing Gristle, Fad Gadget, stuff like that—and that basically led me into techno. Those two worlds are so closely connected it’s unreal. Post-punk, industrial, new wave: to me it all really relates to techno.”

So were industrial flavours always part of Cayzer and Roberts’ tastes, or a recent discovery? “I think both of us come from a background that relates to industrial music, more so, you could say, than our dubsteppy and garage tracks,” Roberts says. “Cabaret Voltaire were a pivotal moment for me. From there I found Throbbing Gristle, Fad Gadget, stuff like that—and that basically led me into techno. Those two worlds are so closely connected it’s unreal. Post-punk, industrial, new wave: to me it all really relates to techno.”

I’m reminded of a young Karl “Regis” O’Connor bringing his post-punk and industrial-informed ethos to bear on the techno framework, resulting in the Downwards imprint. Indeed, both Cayzer and Roberts profess a strong admiration for the Birmingham sound of Regis, Surgeon and Female. As an influence, it’s clearly audible in their more conventional productions (the storming “Clean It Up”), but also pervades their work in a subtler manner: in its grubby surfaces, tightly controlled aggression and revolutionary bent. Perhaps it’s no surprise, then, that Surgeon is an admirer. A collaborative EP between Roberts and the veteran producer, under the name Trade, was released this month on Sheworks.

In fact, Trade is only the most visible evidence of Anthony Child’s engagement with the UK’s new school. He agrees that UK techno is in a more exciting place now than it has been for a while. “Currently I find it easy to DJ a whole set of brand new music, all of which I’m really feeling,” he says. “That’s a situation I don’t remember since perhaps the late ’90s.” Child’s influence looms large over this new generation, both from his solo output throughout the ’90s and early ’00s, and his collaboration with Regis as British Murder Boys. For Child, though, this isn’t a case of giving the nod to second generation imitators. “There’s always a new and different energy to [these new productions], which I really enjoy. I can hear musical reference points, yet it’s music that could only exist right now. That’s what’s so great about it.”

Still, it feels appropriate that Child and O’Connor should choose this year to revive British Murder Boys—dormant since 2008—given that its remorseless breakbeat-led clangour can be heard in much of this new music, from Perc’s “A New Brutality” to MPIA3’s “Your Orders.” Child downplays the timing of the reunion. “From my point of view, the reason Karl and I have started making music together again is due to our friendship much more than any external factors. It’s funny, Karl reminded me that the first incarnation of British Murder Boys was at the height of the popularity of minimal techno. What we did was almost the complete opposite of what was popular at that time.”

The situation couldn’t be more different this time around, with a new BMB EP, Where Pail Limbs Lie, emerging late last year to wide acclaim. Regardless, we shouldn’t expect the duo to retread old boards. “BMB is following a very different tangent this time that will gradually become clearer,” Child says.

Among those contemporary producers expanding on the possibilities laid out in BMB’s slender but sledgehammer-heavy discography, several find their home on Perc Trax, the label run by Ali Wells, AKA Perc. Wells’ imprint has been showcasing a broad range of techno since 2004, but it seemed to gain a new sense of focus in recent years. Wells cites his discovery, around 2010, of Forward Strategy Group, Sawf, Donor and Truss as the catalysts for this new direction. Wells is a vocal fan of industrial music in the broadest sense, taking in both ’90s industrial techno and the original innovators of the ’70s and ’80s (Cabaret Voltaire’s Richard H. Kirk has contributed a remix to the label). It’s a passion evident in the hammer-and-tongs soundworld of his 2011 debut LP, Wicker & Steel, as well as in his A&Ring for Perc Trax. “I see them both as a continuation of the same aesthetic and mindset,” he says of these different iterations of industrial. “It is an attitude to sound, to production and to how music should be released, promoted and performed. There is a DIY element to it and a refusal to give up control or change something to suit the personal taste or commercial interests of someone else.”

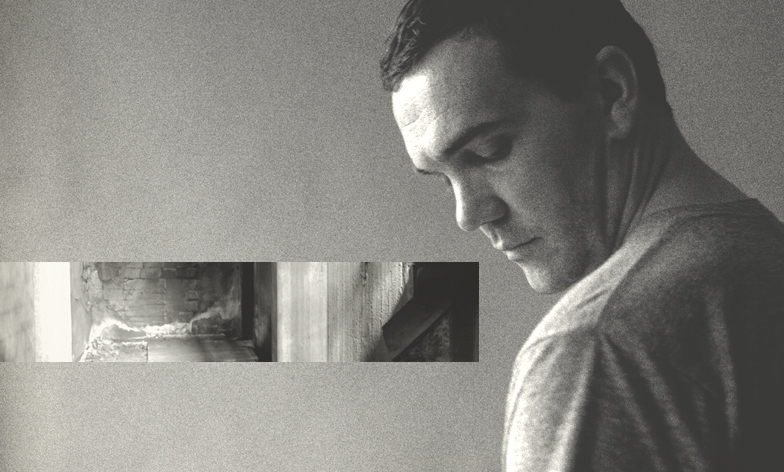

In sonic terms that influence has taken on a distinct form in recent Perc Trax releases, a certain grimness of outlook, perhaps, as well as a distinctly British character that’s more difficult to qualify. Perc Trax affiliate Tom Russell, AKA Truss, offers one of the most distilled and brutal takes on this sound. Past Truss output has tended to be more reserved, but the inauguration of his MPIA3 alias in 2012 heralded a searing new direction. Across releases for Avian and R&S, MPIA3 productions issue a distorted intensity rarely heard in 2013 outside of the much-derided squat rave scene. At their straightest (“Crusty Juice,” “Squatter’s Dog”) these tracks closely mimic ’90s hard-techno, but elsewhere Russell gives them a contemporary, broken-beat twist (“Ridge Way,” “Roly Poly Babs”).

The project, Russell explains, was the product of working with a new, simpler setup. “It’s a very basic setup, pretty much all hardware, analogue-based,” he says, “which means I’m forced to write within a very rigid set of parameters. It’s been a liberating experience and subsequently I’ve written quite a lot more material than I have done in the past.” Inspiration comes from Russell’s raving history. “My roots were in the early ’90s, discovering rave music through my brothers. It was music we’d never heard before, generally UK music, hardcore and early jungle, hardcore techno. At the time it was all on tape, I was too young for the raves, so it was just the DJs that you knew about—people like Stu Allan, Carl Cox, DJ Druid. I’ve only just started finding out who the labels and producers were from that time.”

The project, Russell explains, was the product of working with a new, simpler setup. “It’s a very basic setup, pretty much all hardware, analogue-based,” he says, “which means I’m forced to write within a very rigid set of parameters. It’s been a liberating experience and subsequently I’ve written quite a lot more material than I have done in the past.” Inspiration comes from Russell’s raving history. “My roots were in the early ’90s, discovering rave music through my brothers. It was music we’d never heard before, generally UK music, hardcore and early jungle, hardcore techno. At the time it was all on tape, I was too young for the raves, so it was just the DJs that you knew about—people like Stu Allan, Carl Cox, DJ Druid. I’ve only just started finding out who the labels and producers were from that time.”

While even the Truss material is toughening up (see “Splot” on Our Circula Sound), Russell intends to keep one foot in the cooler climes of his earlier work. It’s a dichotomy—between icy, dub-wise space and pummelling rave-techno—which uncannily mirrors that of Manchester duo AnD, whose recent work, such as the self-released 001/0101, is similarly high-octane. Russell says the correlation was entirely by chance—the two camps only realised their common ground when they began trading tracks a year or so ago. “It was just a pure coincidence that we’d both gone down a harder route,” says Russell. “It was really nice to know there were other people doing it.”

Of course, the music of MPIA3 and AnD—and the nascent scene they are part of—has its detractors. One oft-heard criticism is that this music sounds old, that it’s overly indebted to a sound invented and thoroughly exhausted in the ’90s. Russell is unconcerned with the assessment. “With the MPIA3 stuff I’m not setting out to push anything forward, I’m not reinventing the wheel. I’ve been at my most productive and been making stuff that I’m happiest with when I let go of feeling like I have to bring something new to the table. I’m purely making music that I like and that I would lose my shit to in a club.” Karenn, meanwhile, are keen to emphasise the differences between their music and its ’90s forebears. “I’ve been trying to find older records that sound like the last record we put out and I can’t really,” says Cayzer. “The way I look at it is it’s using older techniques to try and make something that sounds fresh.”

Others find the undiluted aggression of much of this music difficult to stomach. The Perc Trax Bandcamp proudly sports a piece of feedback offered in response to Perc’s “Purple” by UK house duo X-Press 2: “I don’t like this, it sounds like gabba.” Clearly Wells takes an ironic pleasure in the comment, but it nonetheless points to a raft of half-articulated criticisms levelled at the scene: that it is fundamentally shallow, mindless or needlessly macho. Russell, again, isn’t troubled. “I’m absolutely fine with [that criticism]. I’m not trying to pretend that [my music is] anything other than what it is, and it is mindless music. But that’s a beautiful thing, and that’s no less valuable or less relevant than other artforms.” Roberts is similarly sanguine about current tastes. “It is the extremes of what you can play,” he concedes, referring specifically to MPIA3, “but someone’s got to write those tracks. It’s no less worthy [than other approaches].”

But why do these extremes hold such appeal now? It’s tempting to tie this resurgence of aggression in with a broader movement towards hardness and darkness in electronic music—with labels like Modern Love and Blackest Ever Black leading the charge—and to attribute it to the times in which we live. As with Ryan Diduck’s epithet The New Bleak, the pervasive doom and gloom of the contemporary musical landscape can be read as a reflection of a society struggling under economic collapse and disillusioned with a crumbling political system. Wells’ decision to package Perc EP A New Brutality with an image of Trellick Tower, perhaps London’s best known piece of Brutalist architecture, when viewed alongside the social commentary of titles like “Cash 4 Gold,” seems to take on a political dimension.

However, Wells is wary of links between the musical and the political. “I don’t see a news report about a downturn in the British economy, or the 100% cut in arts funding in Newcastle, and then run to the studio to express my anger in the form of a techno track,” he says. “My energy would be far better spent playing an active role in campaigning, protesting and raising awareness, not making a track to keep Berghain moving at nine in the morning.”

In reality, the basis of this new movement is more likely to be found in the aesthetic revolutions and counter-revolutions that animate any music scene. Wells partly attributes his move towards a drier, more spartan sound to being “bored to death” with a predominating “drone techno sound,” while Russell bemoans the tendency in much recent techno for it to “crawl up its own arse a little bit, trying to be conceptual, people trying to analyse a deeper meaning [in it]. It’s fine if people want to do that, but for me, rave music’s never been about that—and I view techno as being rave music.” Cayzer and Roberts, meanwhile, see their new sound as part of a natural process of exploration as the post-dubstep movement that birthed them loses impetus. “The same [is happening] with a lot of people in that scene,” Roberts points out. “Maybe it’s losing a bit of steam because people are experimenting with different sounds, taking it somewhere else.”

And where is this spirit of experimentation likely to take them next? Where the more distilled versions of this sound are concerned (AnD and MPIA3 in particular), it’s difficult to imagine a continuation of the same creative vector, although when asked about the duo’s future direction in a recent LWE interview, AnD’s Dimitri replied, “It’s all about getting hard man, harder and harder and harder.” The statement caused some consternation in techno circles, with many pointing to the burn-out that set in after similar trends in the ’90s. Russell, however, cautions against taking the comment too seriously, and dismisses the notion that the only way is up. “I think if you know the AnD guys, you’d know [that comment] was very much tongue-in-cheek. I don’t think there should be any concern about things getting harder. I think it’s just a really healthy thing at the moment to try and explore all different avenues.” Roberts echoes the sentiment, suggesting that the sound is still in its infancy. “I think it just needs a bit of time. We’ve only just got started. We want to have another year where we can really cement what we want to do. It’s nowhere near peaked yet.”

Source: RA

Truss – Will Darkin

Trellick Tower – Thomas Brauner

Perc – Jimmy Mould